Smyles & Fish asked writers Jerome Charyn and Frederic Tuten to write about their former colleague and friend Donald Barthelme. But what began as a simple look at an influential 20th century literary figure by two of his most notable contemporaries evolved into a portrait in some ways more reflective of the two narrators than of its intended subject. As the project continued, the subject of the piece shifted almost imperceptibly. Like a Barthelme short story, the piece turned inside out, form and content switching places multiple times until these elements became easily interchangeable and finally inextricable. The result, it seems now, is less a portrait of Donald Barthelme, as it is a collage of these three writers and the world of their influences. The picture, complete, fractures. And through the cracks, a new subject emerges: The Collagists.

The cover of Charyn's memoir Bronx Boy features a photo of the author flexing for posterity.

The cover of Tallien, a postmodern memoir-novel of quasi-historical fiction, was painted by David Salle.

The lives of Charyn and Tuten have overlapped at many moments prior to the page they share here. In addition to novels, each has written extensively on art and film, and these respective interests have come to inform their fictional works. Charyn has said of his childhood that the movie house was his library and has thus made a parallel career as a film theorist (teaching American film in the American College of Paris) when he is not at work on another novel.

Resnais and Tuten at a film symposium Tuten organized for The City College in the 1970s.

Charyn's most recent novel, Johnny One-Eye: A Tale of the American Revolution (Norton 2008).

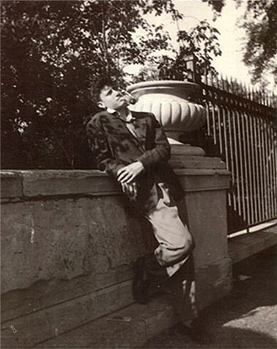

Boy from the Bronx, Tuten, posing for posterity at 17.

Though Charyn has left physically, it seems that imaginatively he is unable or unwilling to resist completely the thrall of his youth. He returns to the Bronx in book after book. Haunted or enraptured by the tumultuous and seductive dangers of the past, Charyn has called the Bronx “the great snake that wrapped around us,” suggesting an ambivalent respect for its capricious bite and strangely alluring venom. Through the music of his fiction, Charyn conjures the snake to rise and dance before us. Taken at his metaphor, if the Bronx is a snake, then Charyn is its charmer. Or do his frequent returns to these memories suggest just the opposite—could it be that the snake is charming him?

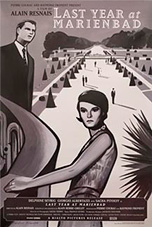

Poster from Alain Resnais' film Last Year at Marienbad, the inspiration for Tuten's short story "The Park Near Marienbad."

Indeed, his next book, part one of a two-part autobiography, is a collection of short fantastical stories in which he, the book’s ostensible subject, is never even mentioned but for the very occasional apparition of a ghostly third-person narrator suddenly made flesh in the rooms where these stories take place.

Tuten in the short film The Year Zero One by Alain Resnais.

Roy Lichtenstein's 1977 Portrait was the inspiration for Tuten's short story "Self Portrait with Cheese."

Fiction is certainly a peculiar manner of memoir. This unusual mode suggests Tuten views his fictional landscapes as a more accurate depiction of himself than any direct memoir could hope to approach. What is real in Tuten’s work is also what is imagined. Storytelling and storyliving are interchangeable after a time, and inextricable. As the body and brain combine to suggest a mind, so does the mind at work suggest the imagination, suggest the soul, to which Tuten so often refers. Tuten’s self portraits might be object lessons. The reader of these “Self Portraits” is asked to see Tuten as the writer at work. His fictional creations, the manifestations of his soul, his worlds suggest his existence through their existence. The story, any story, is thus an extension of the self. Fiction is a protracted self-portrait, he seems to be saying with this latest collection. Fiction is the shroud over a body laid bare.

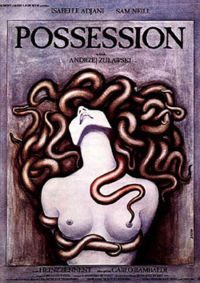

Possession (1981), a film written by Żuławski and Tuten, boasted an international cast including French movie star Isabelle Adjani and New Zealand leading man Sam Neill, as well as a monster designed by Carlo Rambaldi, best known for his his creation of the title character in Steven Spielberg's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and special-effects work on Ridley Scott's Alien

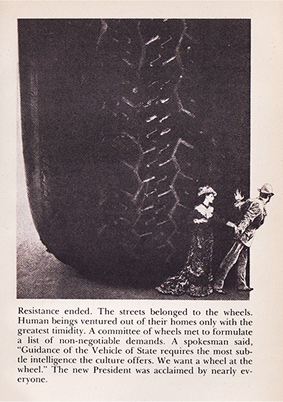

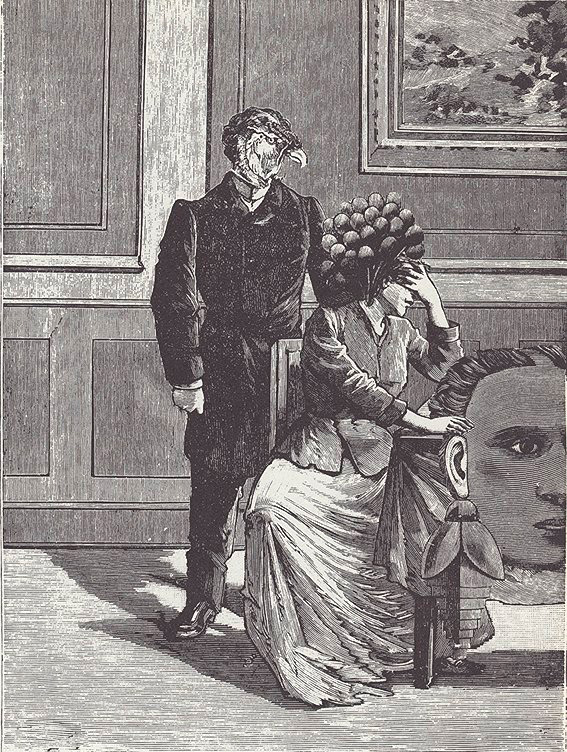

An excerpt from Barthelme's collage story "A Nation of Wheels." From Guilty Pleasures.

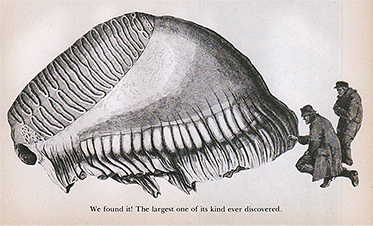

An excerpt from Barthelme's collage story "The Expedition." From Guilty Pleasures.

In Jerome Charyn’s essay, Charyn offers a personal look back at his brief tenure as Barthelme’s accomplice, when together with Mark Mirsky, Faith Sale and some others, they began Fiction magazine. However, through his narrative we also learn a little bit more about Charyn himself. Tuten, meanwhile, chooses to look back by looking elsewhere. By assembling fragments of Barthelme’s oeuvre to work in conjunction with glued reproductions of his most beloved paintings, Tuten unveils a bizarre self-portrait with his response. Perhaps refraction is the nature of reflection and so it would be impossible for light not to bounce back and elsewhere, creating accidental targets. For, as Charyn and Tuten reflect on Donald Barthelme and the nature of his project, glimpses of their own lives emerge and their dreams poke through the fault lines of the collage.

In Tuten’s novel Tallien, the narrator, quoting the 17th century painter Claude Lorrain, says, “The foreground in a picture is always unattractive and art demands that the interest of the canvas should be placed in the far distance, where lies take refuge, those dreams which blossom out of fact and are man’s only love.” The novel has at its foreground the story of Tallien, the French revolutionary, told in an imagined speech delivered to the father from the son. What is the book about? Bringing this to bear on our collage assembled here, the question is plain: Which is the foreground, our designated subject? And that which we see receding in the distance, is it more or less important? The figures of this piece alternately emerge from and retreat into the background, the foreground and background becoming almost interchangeable. Thus, is there a definitive subject in all of this? And is that subject, too, just a mirror back? The suggestion of a hand at work? Are all works of art self-portraits finally? The question cannot be put off any longer: Is all literature about me?

Charyn, Tuten and Barthelme illuminate and confuse this question in each of their works, as they give us stories in which we find our own hearts as well, tales in which we find echoes of our deepest selves, scenes depicting eternal gestures that have been or will be made if at least once by our own hand or with our own eyes, or in the way we might one day cast a face toward the sea at a dusk come too quick, or when we stand at street level above the Paris Metro and feel the rumble underfoot of a train escaped from the Bronx, or in a glance toward a woman who only ever arrives, or a look back—

-Iris Smyles

I never really knew him well. I knew him, and that was enough. He looked like Ahab with his grizzled beard. But he wrote like Jonathan Swift, with a pinch of Rimbaud. I remember the first “compliment” he ever paid me. I’d given him a novel of mine, about a homicide detective who dies in the middle of a ping-pong match. He promised to read it, and he did. “A good genre novel,” he said, stroking his beard. “I could only find one or two clinkers”—meaning bad sentences. You could not find one clinker in anything he ever wrote.

Donald Barthalme in 1980 / Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab

Nothing escaped his savage wit—fathers, dead or alive; Snow White; Alice B. Toklas; Captain Kidd. He had an echolalia that mimicked all our voices, all our desires. But he was most savage with himself. I rarely saw him smile, except at his own foibles.

He was stingy with his praise, but when he did love something, he loved it like a priest, with a devotion that was absolute. Barthelme was one of the first to read Gabriel García Márquez, and he imposed his priestly legislation upon me: I could either read One Hundred Years of Solitude, or never talk to him again. I was caught up in the dream of Macondo for an entire month, and I never really recovered from that book.

I could understand Barthelme’s devotion to One Hundred Years of Solitude—it was like a dueling mirror to his own work. If García Márquez’s writing was about the ultimate expanse of the imagination, Barthleme’s was about its ultimate contraction. He’d narrowed language down to a murderous pin (with a lot of prickles).

Barthelme emerged in the 1960s as our most original storyteller. He’d revised and remapped the whole literary landscape. He was always being imitated. Barthelme clones appeared almost as soon as Barthelme himself. And if he ended up in a state of exhaustion, that’s because he left himself so little wiggle room and no escape routes. His entire oeuvre was an attack upon the novel, with its digressions and swollen joints, yet he too wrote novels, as if he had to participate in his own evisceration. He was also an incredible maker of collages, and that’s how I was introduced to him.

Barthleme pretended that he did not take part in the editorial process, that he was simply helping to design the magazine and might happen to look over our shoulders from time to time like a sympathetic Santa. But Mirsky and I were forever politicking, maneuvering around Barthelme, and once we happened to slip a story under his radar—it was by one of our former professors, someone we admired; it wasn’t a bad story, but it did have a number of “clinkers.” Barthelme raged like Ahab when he saw the story in print. And he removed himself from our editorial board. Like deceitful children, we had let him down.

But our fall was inevitable, I think. We would have disappointed him in some other fashion. We connived too much, took too much glee in our little games. After that, the magazine continued to chug along, but without those wonderful Barthelme covers. No more Little Red Riding Hoods. No more Marcel Proust. Yet that could also have been Barthleme on the wallpaper, behind Red Riding Hood, with a beard rather than a moustache, and with a seriousness and corrosive wit that seemed to shame us all.

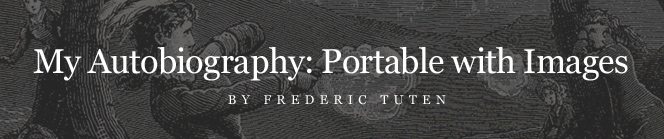

When I was young, I imagined that I could see history through a sluice in a gate, and with the power of my vision I could alter and shape the course of history. I was young and did not then know that “history always takes place behindone’sback. As your gaze is fixed upon something immediately in front of you… history makes a slight, almost imperceptible slither, or shudder, in a direction of its own choice.”

Donald Barthelme. “The Angry Young Man.” Guilty Pleasures (43). Max Ernst. UneSemaine de Bonte (119).

I came to know him in 1971, shortly after publishing my first novel, TheAdventures of Mao on the Long March, a book made of quotes taken from various sources combined with my parodies of American writers and of the then current art criticism. It is a novel made up of fragments cohered around the unifying spine of a rather straightforward narrative describing Mao and his army’s 9000-mile foot-marched flight across China to safe havens in the caves of Yanan.

But this knowledge of history did not deflect my sadness. She saw my whole despair and, one afternoon as I returned home from the club, she said: “Perhaps even now it is not too late. Change style. Learn to snap. Leave government service, plunge into jungles of commerce.”

Donald Barthelme. “Snap Snap.” Guilty Pleasures (33). Max Ernst. UneSemaine de Bonte (107).

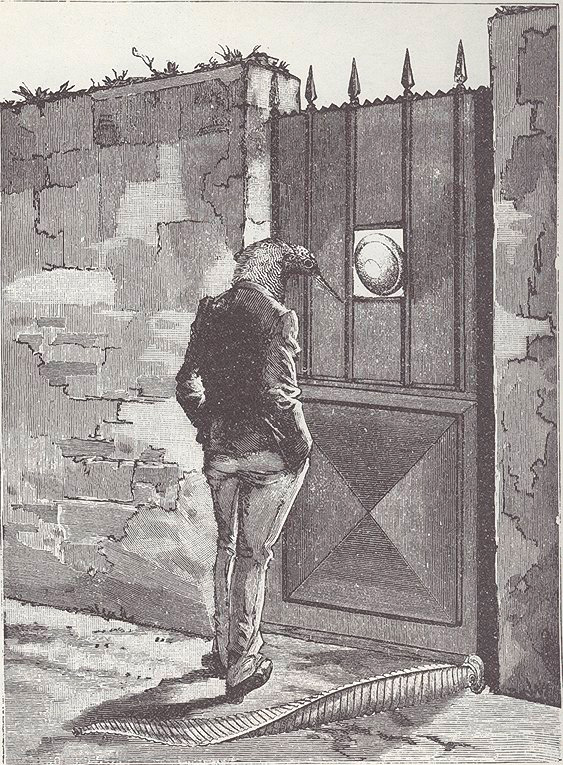

Even the world of cash and trade, with all its excitements of loss and gain did not improve my disposition. One day, as the tide of evening flowed into our bedroom, I thought I saw a light, one which did not please her.

“‘Relax, Amanda,’” I said. “‘We can lick this thing. Just trust me.’”

“‘What do you propose?’ she asked, her brilliant aqua eyes full of fondness and eye shadow. ‘What?’”

“‘New games,’ I said. ‘New games, Amanda, to set the turkey of mental excitement flying through the thin air of intellectual irresponsibility.’”

Donald Barthelme. “Games are the Enemies of Beauty, Truth, and Sleep, Amanda Said.” Guilty Pleasures (130). Max Ernst. UneSemaine de Bonte (63).

I wanted to make this collage in homage to Donald Barthleme for his influence on me as a young writer, years ago, in showing that there were many ways of telling a story. And that subject matter could come from anywhere, even comic books as well as the material of one’s life. His story about Batman and Robin, “The Joker’s Last Laugh,” was especially rich in that conception because it indicated that one could make a fiction winnowed away from the trails of autobiography, from politics, from ideas. Of course, this idea is itself a fiction.

So I set about to discover new pleasures—guilty or otherwise—and fresh adventures. I found that life, in its most ecstatic moments, yielded me nothing as much as the “poetic passion, the desire of beauty, the love of art for art’s sake.”

Walter Pater. “Conclusion.” StudiesintheRenaissance, as found in The Adventuresof Mao on the Long March (78). Max Ernst. UneSemaine de Bonte, (175).

I wanted to make a collage using the troubling images from Max Ernst’s book, UneSemaine de Bonte, and bind them to lines from some of Barthelme’s stories, hoping to create from that blend a work wholly mine yet wholly anchored in the works of those two artists, both vivid presences in my life.

I had traveled up and down the world in search of its aesthetic treasures, but after some years I wearied of art and its joys, wanting a greater and deeper meaning as to why I was alive and why I should want to remain so. All passion seemed to vanish from the earth and I turned to the heavens and to the moon, especially, hoping to find in its radiance some glow of celestial warmth.

After many years of moon-gazing, I finally returned home to tell her my conclusion to my last hope.

“Let’s face it bravely,” I said. “‘See the moon? It hates us.’”

Donald Barthelme. “See The Moon?” Sixty Stories. Max Ernst. UneSemaine de Bonte (133).

Finally, I wanted to compose a work to say to Barthelme what in the time I knew him I did not have the temerity to say, and to send him an affectionate salute.